Your Custom Text Here

Becoming Lithocene (2019) curated by Diana Hierbet at Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity.

Tsēmā Igharas / Suzanne Nacha / Meghan Price / Hannah Rowan

Becoming Lithocene pulls from the language of speculative storytelling and glacial geology to approach the actual and imagined relationships between ice and rocks present in this exhibition. Lithocene, a term coined by contemporary medievalist and environmental humanist Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, is used in this exhibition as an imaginative proposition to describe a longer view of lithic lifespans, and their ability to link and transcend human epochs. As theorist Lowell Duckert writes in his 2013 essay, Glacier, “to study a glacier is always to study its work. A glacier is always-already acting, and its work is never done.” [1] Speaking to the unfixed state of the geologic, the works in Becoming Lithocene serve as explorations of vast geologic time, while also pointing to questions of memory and place via the geological relationship between these two materials.

The assembled works serve as an invitation to rethink the temporal structures that appear to ground cultures and geographies. Ice is creaturely and ephemeral, destabilizing and depositing rocks before it disappears. Forming rafts that suspend, displace, and transport, it is responsible for the movement of pebbles, boulders, and mountain ranges. In the context of this exhibition, such partnerships between ice and rock are observed through the geologic movement of the glacial erratic—a rock deposited by glacial ice non-local to its area—that is referenced in three works by Meghan Price. Small diorama-like boxes contain stones enmeshed in metal netting. Released from their environment, some seem tenuously held in an abstracted landscape, while others appear to have moved at a quicker rate. Works by Price and collaborator Suzanne Nacha draw attention to the unfixed state of glacial erratics by making impressions of their surfaces and flying them as kites; a floating topography of past or future geographies.

Tsēmā Igharas’ sculptural photographs depict black and green obsidian, traditionally mined by Tahltan First Nation from the volcanic complex Mount Edziza in what is now known as northwestern British Columbia. Familiarly known as Ice Mountain for its prominent ice-filled caldera which creates its own weather systems, the mined obsidian from Mount Edziza in Igharas’ work evinces its geological history as well as a culturally grounded understanding of the material. As a form of volcanic glass created by fissures or erupting volcanos that cool in water present on the mountain, obsidian also reflects a particular geological relationship between rock and ice in liquid form. The artist’s choice to install these works of proxy obsidian on the ground speaks to their past lives rooted to the Mount Edziza region, as well as the Tahltan connection to the land.

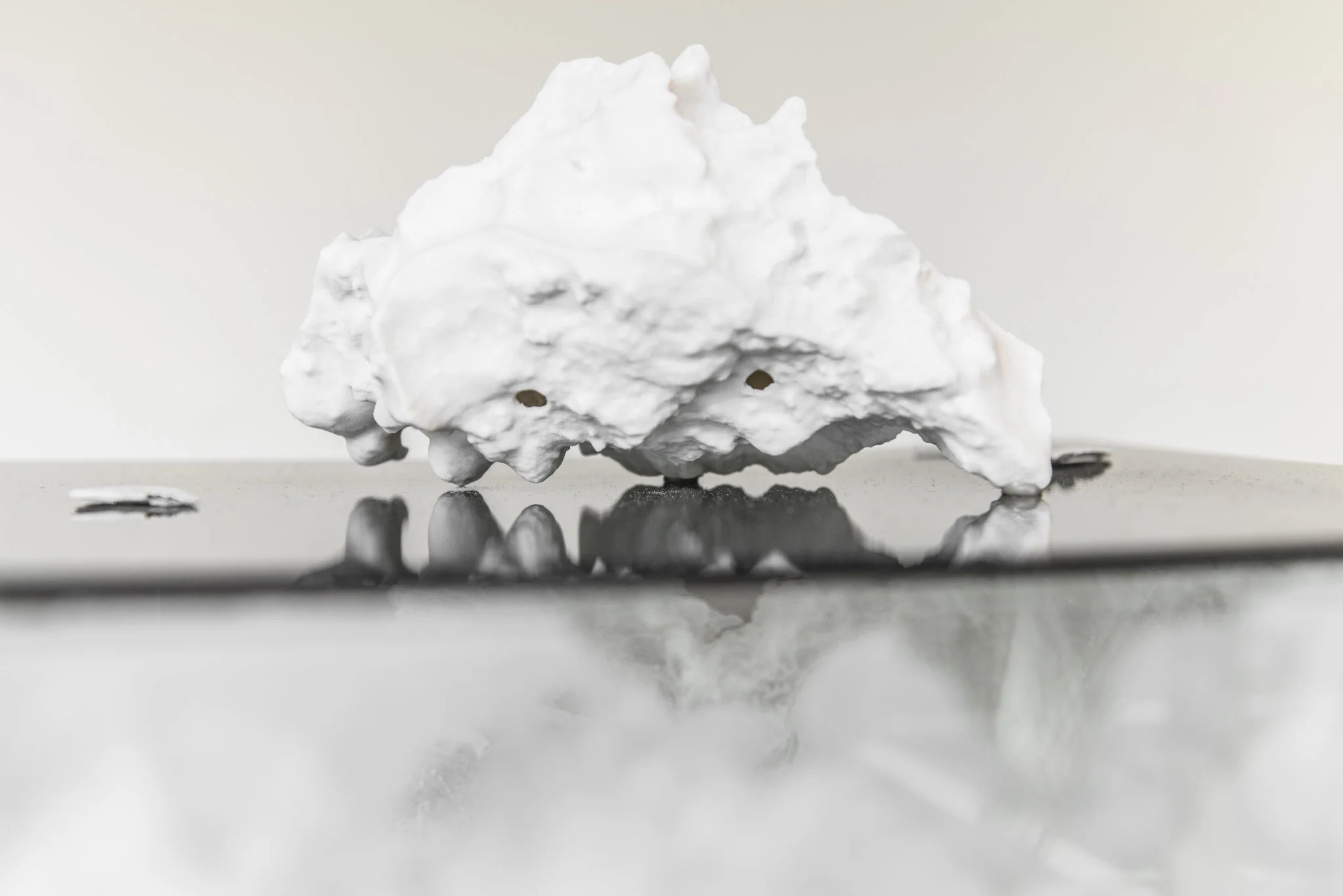

Hannah Rowan draws attention to the individual physical properties of copper, plastic, ice, and their imbued material histories that work to reposition the anthropocentric binary between human and nonhuman. These sculptural installations could be understood as cumulative in a temporal and physical sense: instead of sediment, active layers such as the movement of melting ice; the formation of salt crystals; and water piped to and from a tank, reflect the artist’s interest in visualizing ‘a continual state of becoming’.[2]

This exhibition’s reference to the Lithocene represents an effort to look back as well as forward, to destabilize anthropocentrism, and to partner with forces outside of human experience. In storying fluid interactions between ice and rocks, each work in Becoming Lithocene calls attention to the ways in which nonhuman and human lives will continue to overlap and shape one another.

Curated by Diana Hiebert, Curatorial Research Practicum at Walter Phillips Gallery.

[1] Lowell Duckert, “Glacier,” postmedieval: a journal of medieval cultural studies 4, no. 1 (2013): 71. doi:10.1057/pmed.2012.41.

[2] Hannah Rowan, in conversation with the curator, 2018.

text by Diana Hierbet and Photography by Nahanni McKay.

Becoming Lithocene (2019) curated by Diana Hierbet at Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity.

Tsēmā Igharas / Suzanne Nacha / Meghan Price / Hannah Rowan

Becoming Lithocene pulls from the language of speculative storytelling and glacial geology to approach the actual and imagined relationships between ice and rocks present in this exhibition. Lithocene, a term coined by contemporary medievalist and environmental humanist Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, is used in this exhibition as an imaginative proposition to describe a longer view of lithic lifespans, and their ability to link and transcend human epochs. As theorist Lowell Duckert writes in his 2013 essay, Glacier, “to study a glacier is always to study its work. A glacier is always-already acting, and its work is never done.” [1] Speaking to the unfixed state of the geologic, the works in Becoming Lithocene serve as explorations of vast geologic time, while also pointing to questions of memory and place via the geological relationship between these two materials.

The assembled works serve as an invitation to rethink the temporal structures that appear to ground cultures and geographies. Ice is creaturely and ephemeral, destabilizing and depositing rocks before it disappears. Forming rafts that suspend, displace, and transport, it is responsible for the movement of pebbles, boulders, and mountain ranges. In the context of this exhibition, such partnerships between ice and rock are observed through the geologic movement of the glacial erratic—a rock deposited by glacial ice non-local to its area—that is referenced in three works by Meghan Price. Small diorama-like boxes contain stones enmeshed in metal netting. Released from their environment, some seem tenuously held in an abstracted landscape, while others appear to have moved at a quicker rate. Works by Price and collaborator Suzanne Nacha draw attention to the unfixed state of glacial erratics by making impressions of their surfaces and flying them as kites; a floating topography of past or future geographies.

Tsēmā Igharas’ sculptural photographs depict black and green obsidian, traditionally mined by Tahltan First Nation from the volcanic complex Mount Edziza in what is now known as northwestern British Columbia. Familiarly known as Ice Mountain for its prominent ice-filled caldera which creates its own weather systems, the mined obsidian from Mount Edziza in Igharas’ work evinces its geological history as well as a culturally grounded understanding of the material. As a form of volcanic glass created by fissures or erupting volcanos that cool in water present on the mountain, obsidian also reflects a particular geological relationship between rock and ice in liquid form. The artist’s choice to install these works of proxy obsidian on the ground speaks to their past lives rooted to the Mount Edziza region, as well as the Tahltan connection to the land.

Hannah Rowan draws attention to the individual physical properties of copper, plastic, ice, and their imbued material histories that work to reposition the anthropocentric binary between human and nonhuman. These sculptural installations could be understood as cumulative in a temporal and physical sense: instead of sediment, active layers such as the movement of melting ice; the formation of salt crystals; and water piped to and from a tank, reflect the artist’s interest in visualizing ‘a continual state of becoming’.[2]

This exhibition’s reference to the Lithocene represents an effort to look back as well as forward, to destabilize anthropocentrism, and to partner with forces outside of human experience. In storying fluid interactions between ice and rocks, each work in Becoming Lithocene calls attention to the ways in which nonhuman and human lives will continue to overlap and shape one another.

Curated by Diana Hiebert, Curatorial Research Practicum at Walter Phillips Gallery.

[1] Lowell Duckert, “Glacier,” postmedieval: a journal of medieval cultural studies 4, no. 1 (2013): 71. doi:10.1057/pmed.2012.41.

[2] Hannah Rowan, in conversation with the curator, 2018.

text by Diana Hierbet and Photography by Nahanni McKay.