Hannah Rowan, Prima Materia, edition of 400, litho print on recycled paper.

published by Assembly Point in collaboration with Lena Wurz, with a specially commissioned essay by Thomas Pringle ‘Refraction of Light in Water’

and extracts from Esther Leslie. more info here

physical copies available on request, please use contact page if you would like a copy

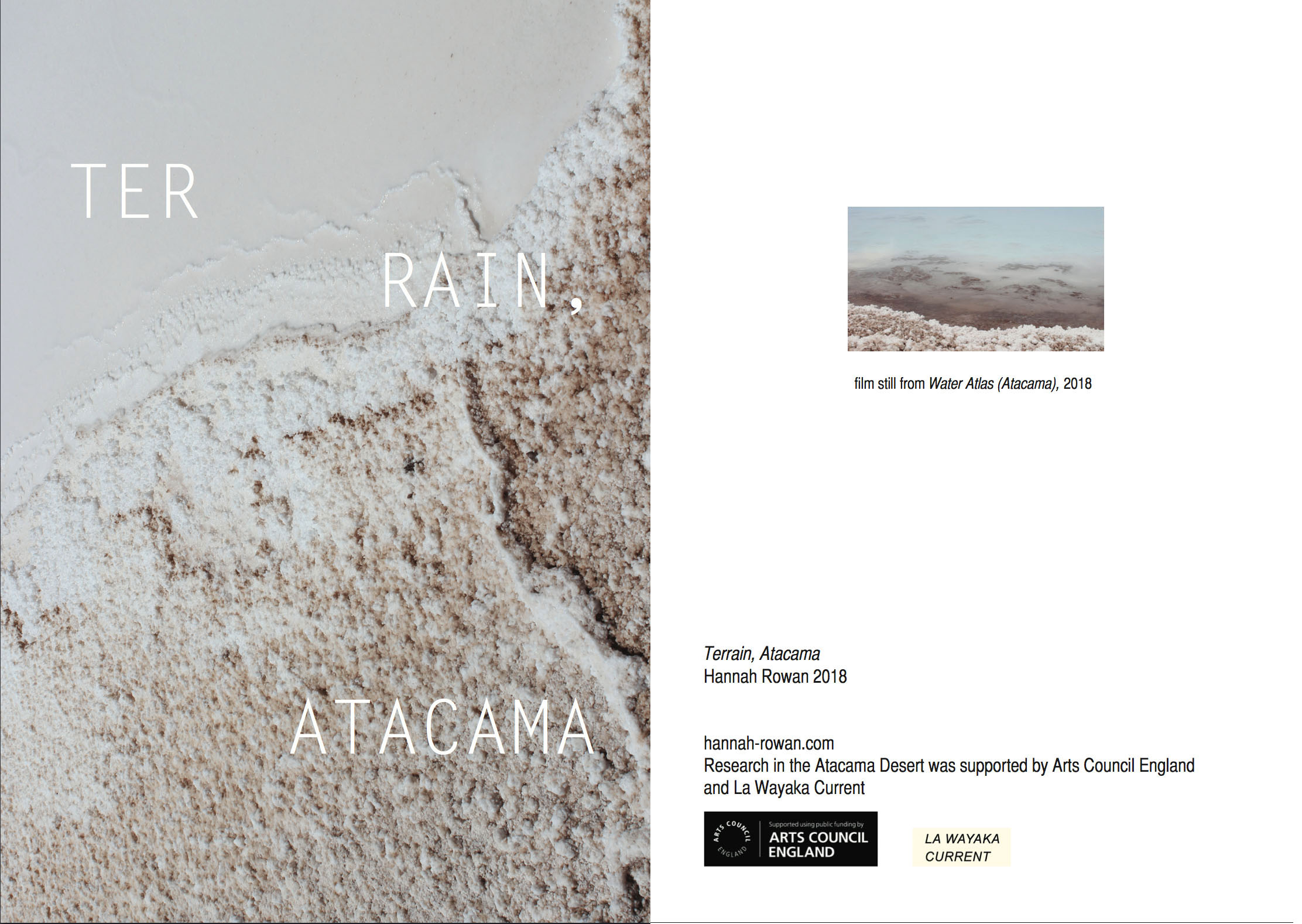

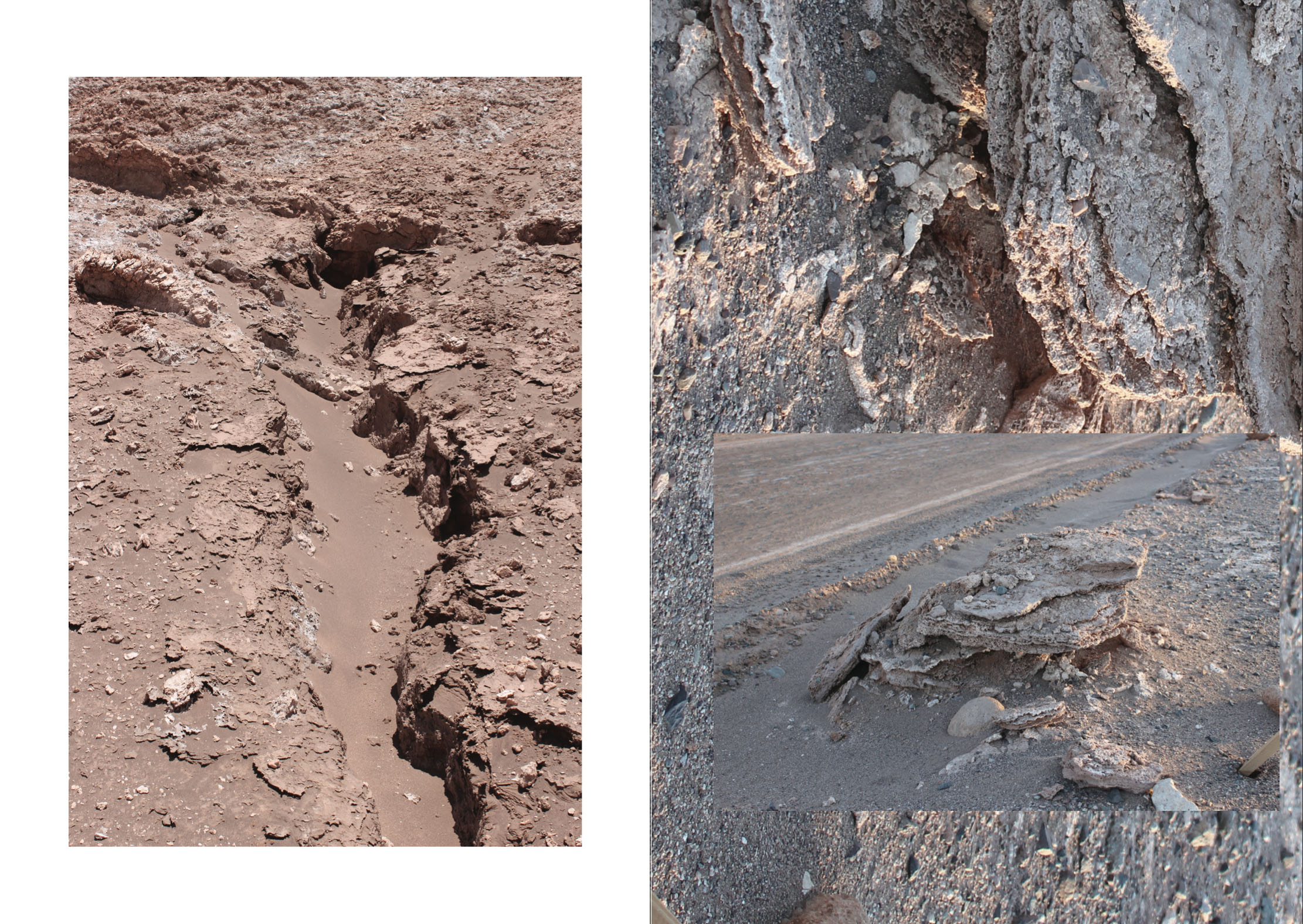

TERRAIN, ATACAMA

Hannah Rowan, 2018, 32 page book, printed as an edition of 50. viewable PDF below, book available on request.

EARTH ISSUE VOL III

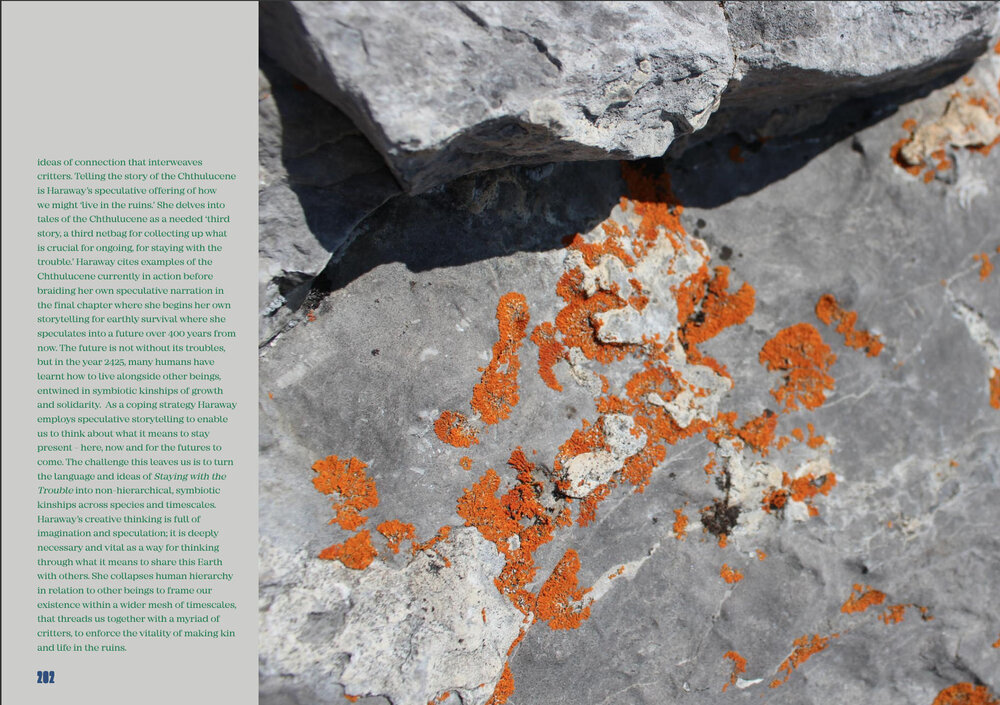

From the Earth Issue Bookshelf: Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. A book review by Hannah Rowan.

Earth Issue vol III, Available to view online, print version still available to purchase here

Hannah Rowan Featured in Elysian Magazine

INTERVIEW with DATEAGEL ART

(view here)

Constructing precarious ecologies on the edge of expansion or the brink of collapse.

SEARCHING FOR WATER IN THE ATACAMA DESERT TEXT BY GEORGE BRAY

In November 2017, artist and writer George Bray interviewed Hannah Rowan in her studio to discuss her work, research and influences. Shortly afterwards, Rowan departed for a research trip to the Atacama Desert, Chile, the driest place on earth. They met again in the summer of 2018, to discuss the influence this time in the Desert has had on her recent work and an upcoming show with La Wayaka Current at Guest Projects. The below text is written by George Bray in response to their conversation, with images from Hannah Rowan.

Chuquicamata copper mine located in the Atacama Desert, Hannah Rowan.

Searching for Water in the Atacama Desert

Aerial View of Atacama Desert, Hannah Rowan.

Hannah Rowan is an artist who makes sculptural works that meditate on the relationship between the slow geological time of natural processes and the fast paced, technology-driven frenetic activity of humans. She utilises both synthetic and organic materials in her ephemeral, multifaceted constructions; melting ice suspended from metal armatures, salt piles on horizontal planes, liquid tanks, casts, clamps and cabling are all used to make her modular assemblages.

In Autumn 2017, Rowan embarked on an artist-led research project to Chile’s Atacama Desert, in collaboration with La Wayaka Current, an initiative that enables artists to embed themselves within communities living in some of the planet’s most extreme environments. In the Atacama, Rowan spent time with the Likan Antai people, seeking to understand how human activity was affecting the area’s delicately balanced ecosystem and what the consequences were for the lived experience of the indigenous Atacameños.

Salar de Atacama, Hannah Rowan. 2018

Water, in all its shifting states, has been key to much of the artist’s research - melting glaciers, rising sea levels, the effects of water in overabundance. But in the world’s driest desert, the other end of the spectrum came into focus; it’s scarcity in the Atacama makes water acutely sacred to the local community but also has a massive bearing on the economy and politics of the region. Chile produces 43% of the world’s lithium, which is extracted from the brine water that lies just below the desert’s surface, pumped up into massive evaporation fields that stretch across the salt flats for miles. Demand for lithium, valuable due to its central use in rechargeable batteries, has soared in tandem with the digital technology boom of recent decades.

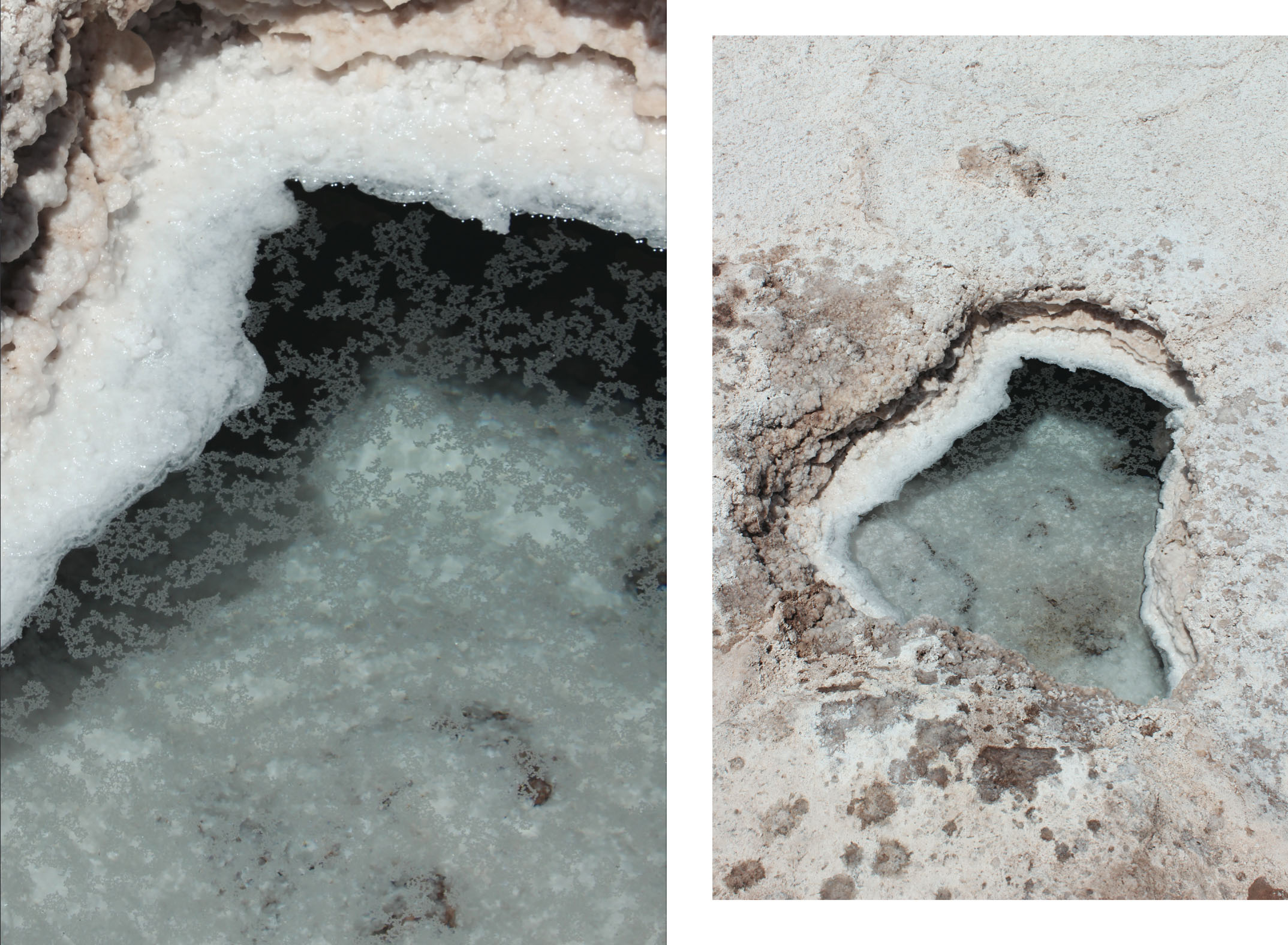

salt lagoon in the Atacama Desert. Hannah Rowan

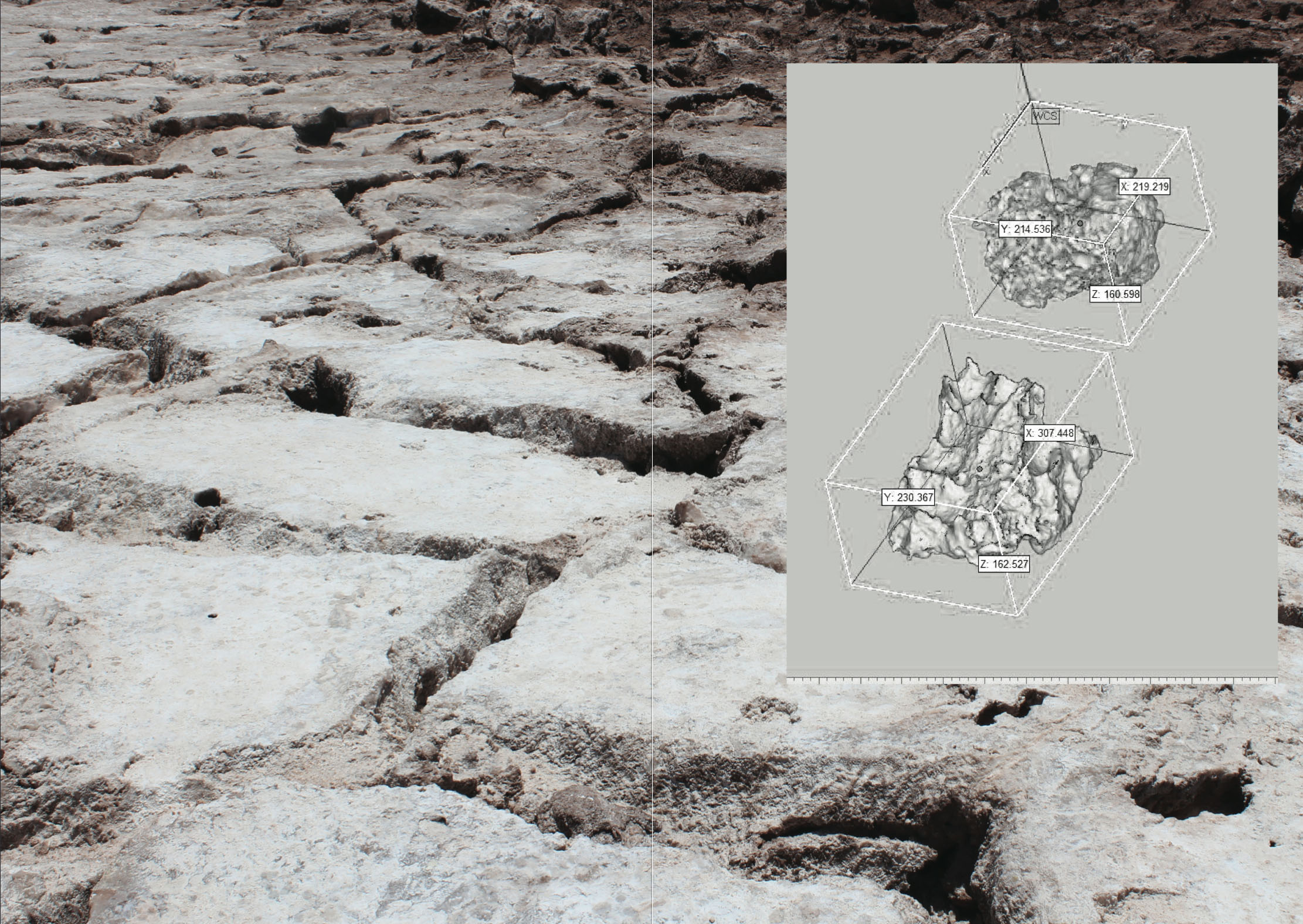

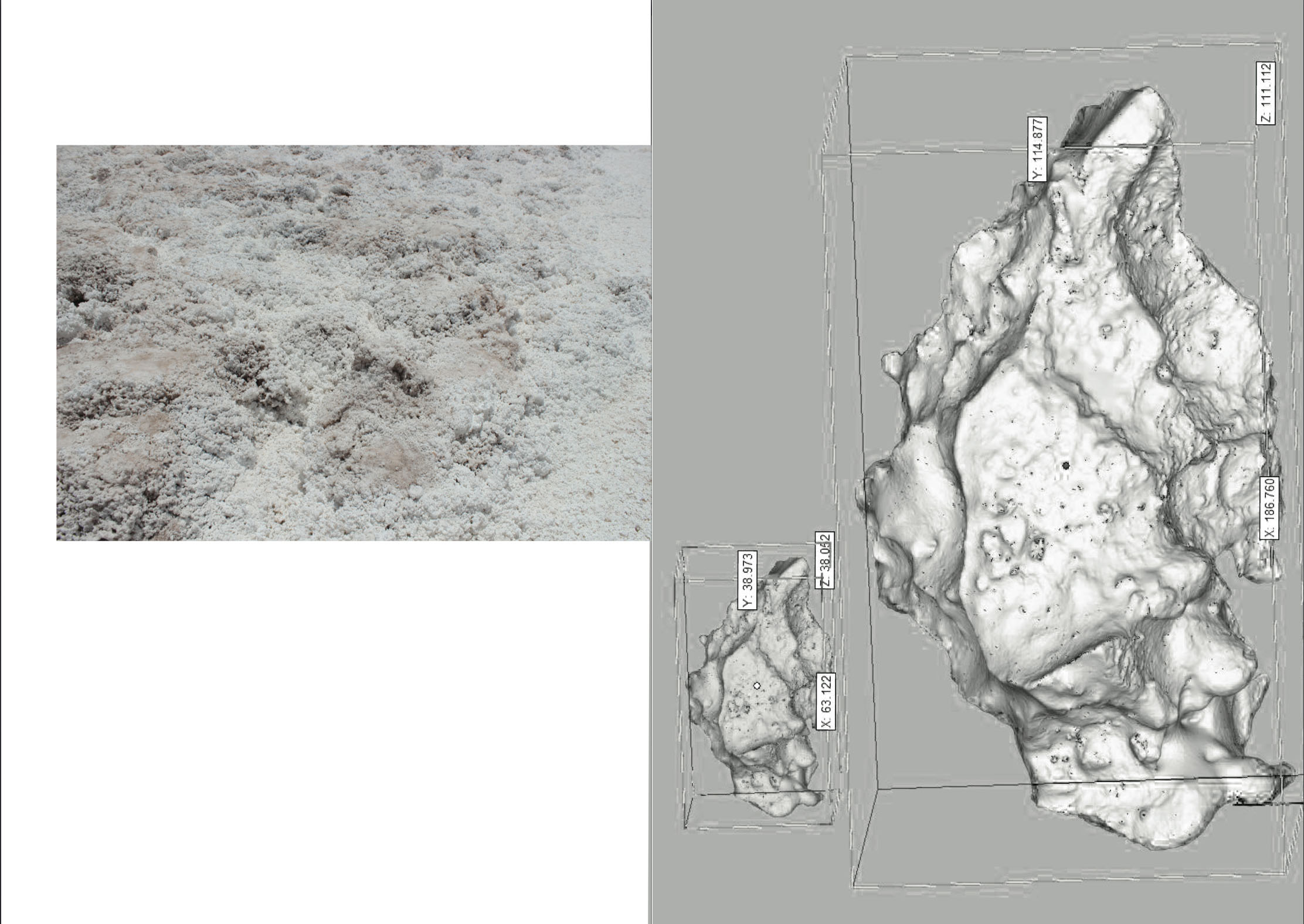

The terrain of the Salar de Atacama, Hannah Rowan

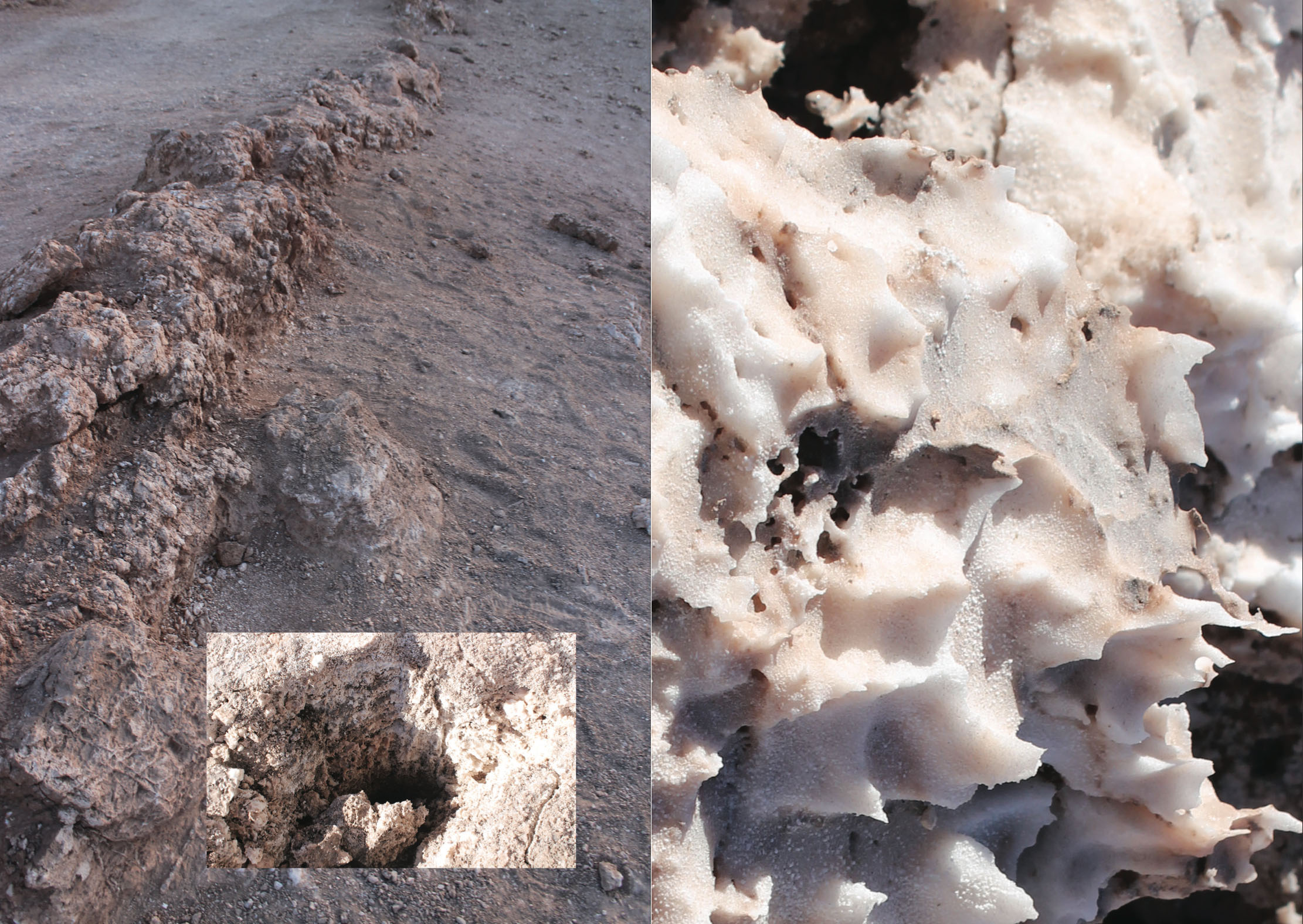

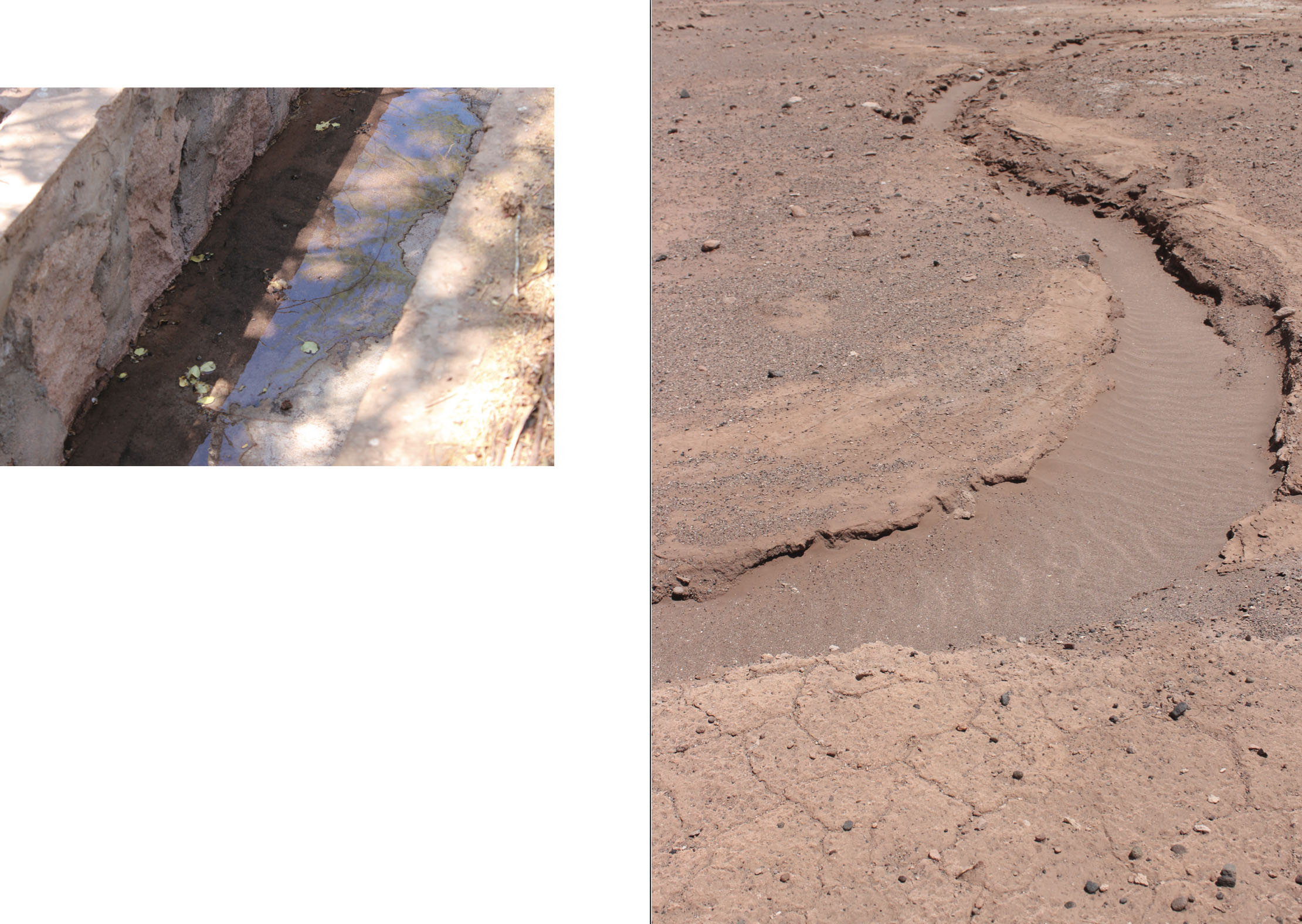

With the mining industry putting increased pressure on an already scant resource, questions of ownership, control and the environmental impact of water became central to Rowan’s research project. As an initial response, she began filming ‘Water Atlas’, documenting the few instances of flowing water that punctuated the barren, harsh white beauty of the desert, from the ancient still-functioning watercourses of the Incas, to the dribbling trickle of a pool pipe that takes days to fill up.

The interplay between natural resources and the advanced technology that relies on their extraction to exist, is interrogated in another series of documenting works, ‘Ghost Relics of the Atacama’: digital scans of the salt rock formations that carpet the desert, recreated in 3D-printed gypsum. These examples of organic material translated into synthetic objects have the feel of pixels made flesh and look like bleached white phantom fossils, physical embodiments of our desire to digitise the environment around us as though subconsciously preparing for a future post-human archaeology.

3D scans of salt crystals, Hannah Rowan, 2018.

3D printed plaster powder salt rocks: Hannah Rowan, Melting Transmission (detail), 2018, image by Oskar Proctor.

Salt Crystals found on the terrain of the Salar de Atacama, Hannah Rowan

Lonely Tree, Hannah Rowan, 2018.

The sparseness of the desert seems to have been incorporated into the rest of Rowan’s sculptural work, made on her return from Chile. The compositions have become more streamlined, pared back, as though eroded by desert winds. Spindly, ossified plant stems have made their way into the mix for the first time and the sculptures now seem stiller and slower somehow. The metal apparatus that make up the bones of the structures feel more clean and clinical – meat hooks and ice screws – as though the natural materials are undergoing some sort of autopsy or are just about to be reanimated in some Frankensteinian experiment.

These concerns with material, technology and the human impact on the world around us are shared by many of the artists who have worked in collaboration with La Wayaka Current, which linked them to remote communities who are already being impacted by rapid changes in climate, in an effort to bring their voices to the fore. In July 2018, Rowan’s work is being shown as part of a showcase of these artists at London’s Guest Projects, an experimental space initiated by the Yinka Shonibare studio.

Rowan, a graduate of the RCA Sculpture programme, is following this with an edition show at Assembly Point, London, before embarking on a second residency at The Banff Centre, Canada, where she was artist in residence in 2016. Next year, she aims to undertake a research trip to the Arctic as part of The Arctic Circle residency, to continue her work on ‘Water Atlas’, mapping the changing geology of one of the globe’s most intensively transforming environments.

George Bray, July 2018

Wild Within, curated by La Wayaka Current will be at Guest Projects, Hackney, London between July 21st - 8th August 2018

Every thing: an Artist Multiples Event at Assembly Point Gallery, Peckham, London 26th-29th July

SQUEEZE IN HERE, HANNAH ROWAN ARTIST FEATURE

Text by George Bray: Interviewed in her studio in October 2017 for Squeeze in Here. Rowan uses a wide array of organic materials and quasi-scientific apparatus to create intriguing, seemingly fragile works that are informed by environmental concerns.

On first entering the studio, you might think you have wandered into a deserted laboratory where the experiments have been left to their own devices. Spindly metal frames are dotted everywhere, supporting angled shelves and transparent surfaces, some carrying Perspex tanks of rippling liquid, others covered in piles of strange, organic substances.

These crystalline heaps are almost spilling over onto a floor that is littered with snaking power cables, scattered rocks and cylindrical plaster casts. The set-up is animated by glowing light bulbs and whirring fans, held in place on jutting armatures by clamps and bulldog clips, interacting with strips of image-laced acetate that stir like plastic caught on a wire fence. Components are linked together with trailing string or wire and are placed at different heights, meaning the eye is drawn from the floor up to nearly the ceiling in an effort to make sense of what’s going on.

The studio is that of London-based artist Hannah Rowan (b.1990) and the multifarious elements on show are typical of those she uses in her work. Everything has a temporary feel, as though it could all be disassembled and reassembled in a rushed 20 minutes. This idea of things lasting for only a limited period of time seems relevant in many ways to Rowan’s work and partly helps to answer that question of what’s going on in her fragmentary installations.Her studio itself is an impermanent one; Rowan is in her final year at the Royal College of Art, occupying the soon to be demolished Sculpture building on the college’s Battersea campus. Since completing her BA five years ago, she has worked in a number of different spaces with finite time limits, a nomadic working practice familiar to many young artists, which has necessitated the lean towards portability in her work.

Another familiarity is the short-term temp job fitted around art-making; Rowan has worked in the past as a set dresser and art department freelancer for film and TV and her experience creating improvised rigs, coupled with a sense of staging and a proficiency with the practical tools of that profession – clamping, taping, lighting, suspending – is evident in her creations.

A need to carve out a separate space for her practice, away from the pressure cooker of London and its frenetic temp work, led her to participate in a number of international residencies, firstly in 2015 at The Banff Centre, Alberta, Canada, and in 2016 at the Vermont Studio Center, VT, followed by the Wassaic Project, NY, both USA. Again spaces with limited timeframes, each residency offered concentrated creative environments that helped focus the interests already present in her work, as well as fostering new ones.

A personal connection with nature, of a type experienced amongst the awesome splendour of the Canadian Rockies, is something Rowan has tried to instil in her work ever since. A closer inspection of her installations reveals how many natural processes are being recreated in microcosm: melting, evaporation, sedimentation, to name a few.

The stratified plaster casts peppering the floor mimic the gradual layering of rock formations. The humming fans send a faint breeze fluttering through the wisps of hanging film. Water, either in excess or scarcity, is a central theme, almost brimming to the lips of the tanks or tellingly absent in the piles of crusted salt crystals. And the pure blue of glacial melt water is the abiding colour present throughout Rowan’s work, often projected using tinted plastic to lace each scene with an icy tinge.

These filmic devices of lighting, projection and wind machines highlight these processes at work, introducing a further element of time – of the viewer having to be present to witness the shimmering optical effects cast by the interaction of light, colour and movement. These carry a sense of spontaneity and visible flux in contrast to the unseen but nevertheless similarly ever present change of evaporating water, drying salt and slow-forming sediment.

Rowan leaves the mechanics of exactly how these effects are created on show, satisfying not just the viewers’ ‘behind-the-scenes’ curiosity but making their artificiality self evident and highlighting their impermanence. By showing how the work can be easily dismantled and reconfigured, a regular occurrence as it is transposed from site to site, the installations seem frail and contingent, as if removing one element would lead everything to collapse. Each structure feels like part of a mutually dependent ecosystem, interconnected by immaterial light and those fragile strands of string.

These works plainly speak to the state of the natural world so present in Rowan’s thinking – not the submissive Romantic awe typified by the likes of Friedrich but a febrile fascination with an environment contending with gigantic ocean trash vortexes, with rampant deforestation and desertification, with mass flooding and sunken habitats.

Actively engaging with this world through her work for Rowan is key and, again, many of the ideas raised can be seen in relation to time and the temporary: from the acceleration of ecological processes due to human activity, to the divergence between immeasurably slow geological time and rapid, technology-driven contemporary existence

And time marches on for Rowan herself. Within a few months she leaves the RCA and, potentially, London as well. In the meantime, another residency in Chile’s Atacama Desert awaits, the driest non-polar desert on Earth – another space to learn, to reflect and to work alongside artists, scientists and indigenous people who share her concern that that the time available to address these shifting states around us is steadily running out.

Text by George Bray, 2017. available at https://squeezeinhere.com/2017/10/30/hannah-rowan/

The Liquid Fragment: Swimming in Data, Drowning in Melting Ice.

Hannah Rowan, 2017, research paper, full version of text available as PDF (upon request)